Among the thirty or so paintings that have survived by Johannes Vermeer, "The Little Street" is a particularly special one and also my favorite.

The vast majority of his works depict indoor scenes and figures, with only one outdoor view, "View of Delft," and this street view close-up. Very little is known about the painter personally or about the background to his works, but it is believed that this painting was executed around 1660 and depicts a street scene in Delft at that time.

The painting is housed in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, in a small alcove adjacent to the "Night Watch" gallery on the ground floor, with four of Vermeer’s small paintings hanging neatly together: "The Little Street," "The Love Letter," "The Milkmaid," and "Woman Reading a Letter." Several contemporaneous Dutch genre paintings are displayed nearby.

Compared to "The Milkmaid" next door, "The Little Street" may not immediately catch the eye, appearing almost like a photograph at first glance. But from the second glance on, one’s gaze may become captivated by it.

Johannes Vermeer, The Little Street

The picture includes two incomplete red brick houses, the one on the right occupying the main part of the picture. The lower part of the street-facing wall is carelessly painted white. The first floor is very high, and the front door opens directly onto a cobbled street. The side door is open, and there is a narrow courtyard beyond the passageway. A shallow drainage ditch runs alongside it.

Delft, like Amsterdam, has a dense canal system, and houses were typically built facing the water. To fit more houses along the canal banks, they developed into narrow, elongated structures with deep interior spaces that were much longer than their facades. In order to maximize natural light, windows and doors were designed to be quite large. Arranging living spaces efficiently within such cramped quarters was not easy, and many Dutch houses of that period were divided into two parts, with the two or three floors at the front serving as a vestibule, living area, and servants’ quarters, and the back containing the main family living quarters. This reminds me of Japanese "nagaya," many of which also had this structure, such as Tadao Ando’s Jukkoku House.

Pieter de Hooch, a contemporary painter of Vermeer’s who also lived in Delft until 1660, was also skilled in depicting scenes of domestic interiors, and it has been suggested that Vermeer drew inspiration from him. From de Hooch’s paintings, one can glimpse more details of the scenes depicted by Vermeer. Their works are often displayed together in museums and art exhibitions.

Pieter de Hooch, 1658

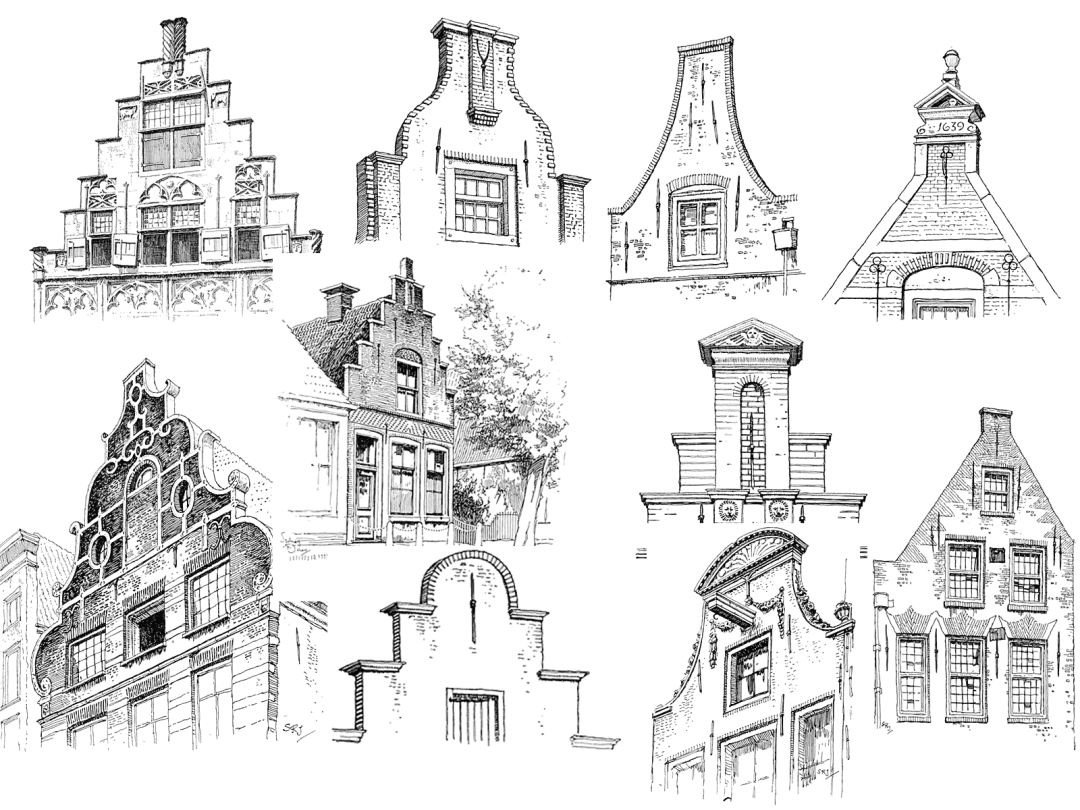

The Netherlands was the first country to extensively use red bricks, which were originally made from the soil dug up to build the canals. By the 17th century, red bricks had become a mature and inexpensive material. The houses in the painting are quite plain, without carved decorations or special wall ties, and feature only simple gable ends and brick arches over the windows and doors. Red brick, gable ends, and the proximity to the river were typical of ordinary Dutch houses of the time. However, experts have also analyzed that the gable end of this house does not feature the slanted or stepped style popular in 17th-century Dutch homes, but instead has deep grooves, suggesting an older architectural style that may have been built earlier.

The gable style of Dutch houses in the 17th century, with iron wall ties hanging on the walls to reinforce the rods inside. Image from "Old Houses in Holland."

Different square-patterned glass is installed on the windows, likely the popular leaded glass of that time, with a relatively dull color. The lower part of the window has a wooden movable shutter that can be opened outward, and the main door also has one. This is a characteristic feature of Dutch houses of that time – requiring ventilation while maintaining some privacy due to facing the street.

The brick walls and windows in the painting appear to be simple brush strokes, with the shapes outlined by lines, and shading and lighting added afterwards. However, the depiction is extremely vivid, as if behind the second-floor windows is a woman writing a letter or a geographer deep in thought.

Another painting I really like is Vermeer’s "Lady Writing a Letter with Her Maid." Of course, the windows, floor tiles, tablecloth, paintings, and clothing of the figures in the painting indicate that this is a scene in a more upscale house and cannot happen in the interior of a "small street" house.

In front of the door is a narrow raised area with colored square stone slabs, and narrow benches are installed on the walls on both sides of the door. This was a simple facility that came with every street-facing house, forming a unique community public space. The door of the house on the left is tightly closed, and Vermeer’s signature is on the wall. The grapevine spreading down adds vitality to the entire picture. According to the researcher’s X-ray analysis of the painting, the red door panel that opens was added by the painter in the later period, adding a touch of balanced agility to the picture.

The composition of the entire painting is unique, with the house on the right occupying a slanted triangular frame and being cut off at the top. At first glance, the focus may be difficult to find, like a casual street scene photo, giving a particularly familiar feeling.

There are four figures in the painting. A woman is sitting at the door, sewing, and another woman is bending over the washbasin in the yard, washing clothes. They both wear white headscarves. Outside the door, two children, a boy and a girl, are playing, their heads close together, staring intently at something on the ground. Although obviously innocent children, they dress much like adults, as there was not much concept of children’s clothing before modern times, and the colors and styles were similar to those of adults. As a Dutch custom at that time, men had to wear hats, and women had to wrap their heads with scarves. Vermeer’s figures in all his paintings are mostly like this.

Dutch ordinary children in a painting by Dutch Golden Age female artist Judith Leyster, showing the children’s dressing style at that time.

The painter’s perspective is noticeably high and distant, much like a view from across the river, creating a voyeuristic feeling familiar to Vermeer’s works. The painter and the viewer are in a corner at a polite distance, quietly peering at undisturbed people in the painting.

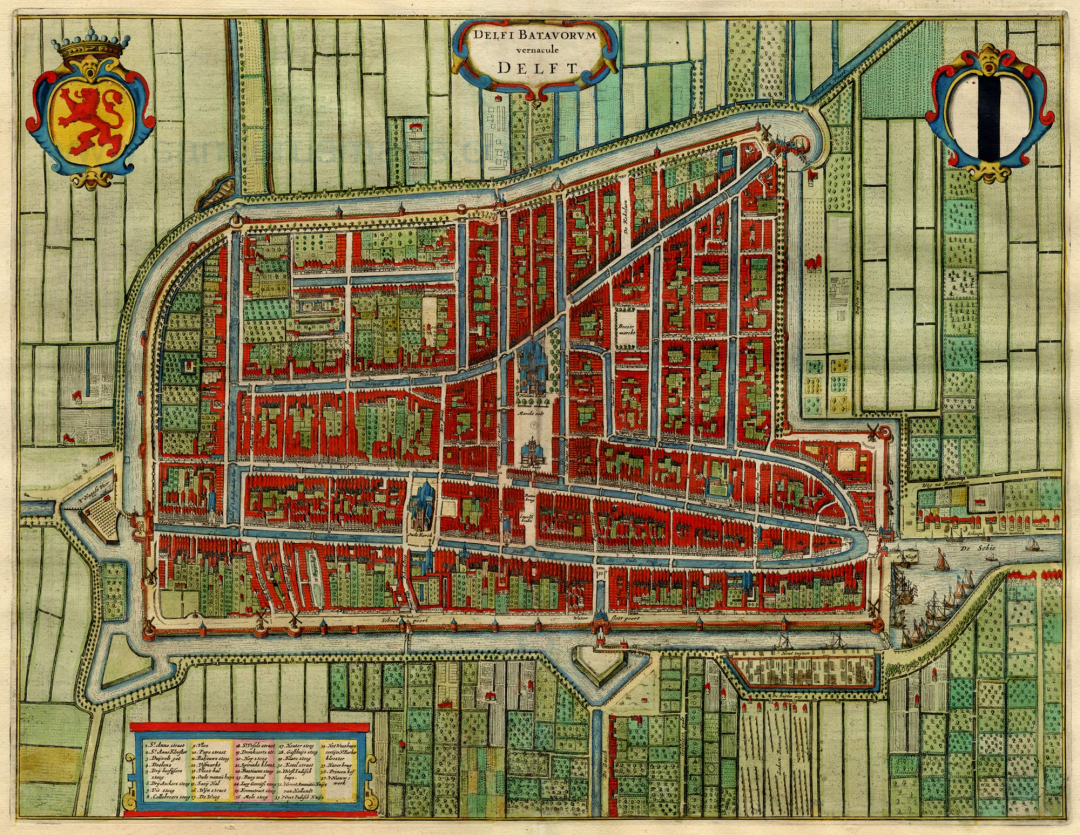

A map of Delft in 1649, by Joan Blaeu

A 1649 map of Delft on Wikipedia, which is close in time to "A Street," shows a network of canals intersecting like main arteries in a city. The structure of the old town remains intact, the two churches are still landmarks of Delft, and of course the city has grown many times over.

Thousands of narrow houses are densely arranged along both sides of the canals on the map. There have been several speculations about where the houses in the painting are located, but the most complete study was announced by art history professor Frans Grijzenhout in 2015, who claimed that the two houses in the painting are located at Vlamingstraat 40 and 42 in present-day Delft. The main evidence is a tax record from 1666, which measures the width of the facades and doors of all houses in Delft, indicating that only these two houses have adjacent side doors, and their dimensions are quite close. Furthermore, according to the study, the houses belonged to Vermeer’s aunt at the time and were not far from his parents’ inn.

Combining the Google Map with the locations of the churches and canals, I found this location on the old map, and the current appearance of this location can be seen in the street view.

Right shows Vlamingstraat 40 and 42 in Delft look like today

At that time, the Netherlands was in its Golden Age, with the development of navigation and technology bringing unprecedented wealth and power to the country, with over 16,000 merchant ships busy shuttling around the world. Delft was a hub of international trade at that time, and Chinese porcelain and Turkish carpets had already begun to appear in residents’ homes. The world in every indoor scene painted by Vermeer was extremely rich, and he must have seen many good things, but this "Street" is simple and peaceful.

Vermeer seems to have painted not for money, as he didn’t have many commissions, but rather for the love of it. His financial situation was poor, as his parents left behind a large inn that was difficult to run, and he also had too many children (11, plus 4 who died in infancy). One can imagine him hiding alone in a chaotic home, silently painting pictures that others couldn’t understand.

However, Vermeer was not a recluse or oddball, and may have been a sociable person. He served on the guild of artists in Delft (the Saint Luke’s guild) for many years, including a stint as its president, and collected works by other artists. He was also a good friend of Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. David Hockney has written a book called "Secret Knowledge", which provides a detailed argument that Vermeer used optical devices to assist in his paintings. These optical devices were likely made by Leeuwenhoek. It’s interesting to imagine a scene from the Dutch Golden Age where the son of a large inn owner is obsessed with painting and a civil servant is passionate about grinding lenses and studying microscopes, and they are good friends. Some people speculate that Vermeer’s "geographer" and "astrologer" were modeled after Leeuwenhoek.

Vermeer was born during the Dutch Golden Age, but unfortunately, this period did not last long. The Franco-Dutch War of 1672 plunged the Netherlands into decline, and Vermeer could no longer sell his paintings. He became increasingly impoverished and died of a sudden illness in 1675.

He was buried in the Old Church in Delft with a brief record: "Johannes Vermeer of Oude Langendijk, leaving behind 8 minor children." 350 years have passed since then, and Vermeer and his world have long since vanished. However, this "Little Street" still quietly tells the story of that moment in time.

Reference

- Arthur K. Wheelock, jr, Vermeer

- Sydney R. Jones, Old Houses in Holland

- Google Arts and Culture

- Wikipedia

- Essential Vermeer

- Rijksmuseum.nl

- Timothy Brook, Vermeer’s Hat